Few stories are as harrowing, or as inspiring, as that of Art Pepper. The alto saxophonist, whose warm, clear and distinctive tone helped define West Coast jazz in the 1950s, was derailed again and again by the scourges of heroin addiction, leading him to years behind bars. But when he emerged from the gates of San Quentin in 1966, and having absorbed the bizarre communal therapy of Synanon, he returned to the jazz scene with a vengeance, creating some of the most emotionally charged music of his life. His post-prison recordings, starting with Living Legend in 1975, stand as testament to a man who transformed personal suffering into transcendent art.

Born in 1925 in Gardena, California, Art Pepper started gigging professionally whilst still a teenager, and he soon caught the ear of band leader Stan Kenton, who made him a featured soloist. In the early 1950s, Pepper was at the top of the West Coast jazz scene, recording landmark albums like Art Pepper Meets the Rhythm Section (1957) with Miles Davis’s rhythm team, and Art Pepper + Eleven (1959) with Marty Paich’s arrangements. His sound was bright yet emotionally vulnerable, and his improvisations carried a natural lyricism that set him apart from the harder edged beboppers of the East Coast.

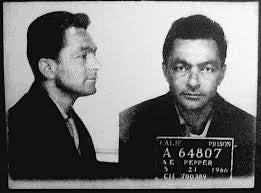

But meanwhile, he fell into the grips of a devastating heroin habit. The lifestyle of after-hours jam sessions, constant touring, and easy access to drugs pushed him further into addiction, eventually leading to multiple arrests. In 1961, after a series of parole violations, Pepper was sent to San Quentin State Prison, where he would stay until 1966.

But behind the scenes, Pepper had fallen into the grip of heroin addiction. The lifestyle of after-hours jam sessions, constant touring, and easy access to drugs pushed him deeper into dependency, eventually leading to multiple arrests. In 1961, after a series of parole violations, he was sent to San Quentin State Prison, where he remained until 1966.

San Quentin was a harsh, dehumanising place where survival was a daily challenge. But even there, Pepper found a way to keep his music alive by performing in the prison band. Those years forced him into a deep reckoning with himself. Stripped of everything but his horn, he confronted the wreckage of his career and his life and began to reflect on what had brought him so low. In his autobiography Straight Life, Pepper wrote that prison “woke me up,” forcing him to face the consequences of his addiction. Whilst being far from a therapeutic environment, San Quentin actually gave him space to gather the fragments of his musical identity, even as his spirit was battered by incarceration.

When he was released in 1966, Pepper faced a world that had moved on without him. Jazz itself was evolving, and he was a felon with few prospects. At this critical moment, he found a controversial lifeline in Synanon a rehabilitation community that used aggressive group therapy sessions, known as “The Game,” to confront residents about their behavior. Synanon had its dark side (and would later be labelled a cult), but it gave Pepper structure, community, and a sense of belonging he had never fully experienced. Within its walls, he learned to stay clean, and to work through guilt, rage, and trauma. He credited Synanon as “the place where I learned to forgive myself”.

Nearly a decade after San Quentin, Pepper re-emerged onto the jazz scene with Living Legend (1975). The title couldn’t have been more fitting: here was a man presumed lost, proving he still had the fire. Backed by Hampton Hawes, Charlie Haden, and Shelly Manne, Pepper played with such urgency and emotional honesty that it startled even longtime fans. Gone was the cool West Coast polish , in its place was raw, searching intensity, forged in the crucible of prison and recovery.

He followed up with The Trip (1976), whose title track evoked his harrowing personal journey. The album balanced beautifully crafted standards with autobiographical originals, revealing Pepper’s ability to channel his pain into art. On No Limit (1977) and Straight Life (1979), he continued to bare his soul both through his blistering alto solos and through the confessional power of his memoir. His tone was now rougher, his phrasing more angular, as if the horn had become a vehicle for exorcising years of regret and rage.

At the heart of Pepper’s story was a struggle with identity. As a white jazz musician who idolised Black artists, he often felt like an outsider in a predominantly Black musical tradition. That tension grew even more complicated during his years in San Quentin, where racial segregation was brutally enforced by prison gangs and authorities alike. Forced to reckon with the boundaries of race behind bars, Pepper emerged with a deeper awareness of his own place in the world and a renewed determination to play jazz with complete honesty. This honesty rings out in his post-prison recordings, which transcend boundaries and speak to the shared human experience of suffering, survival, and hope.

A key turning point in Pepper’s journey came when he shared the bandstand with Sonny Stitt, a towering figure in bebop but to Pepper’s mind, a personal rival. Stitt, a Black alto player rooted in Charlie Parker’s legacy, embodied the very tradition Pepper both revered and feared he might never fully belong to. Their performance together was more than just a gig; it was a moment of personal reckoning. Holding his own against Stitt allowed Pepper to accept his place in the jazz world, acknowledging both the debt he owed to Black innovators and his own right to tell his story through the music. That cathartic confrontation helped free Pepper to play with the unfiltered honesty heard on his post-prison masterpieces.

After 1979, Galaxy Records gave Pepper an opportunity to record prolifically, resulting in a vast series of sessions now collected in The Complete Galaxy Recordings. These albums capture him at the height of his late career powers: fearless, searching, and newly confident. The music ranges from hard-driving bebop to luminous ballads, revealing an artist who had learned to accept both his gifts and his scars.

Pepper’s story is not just personal it reflects a larger truth about jazz culture in the mid 20th century. Many great musicians were swept up in addiction and the revolving door of the criminal justice system. His comeback demonstrated that there was a way back that artistry could survive the worst of circumstances and emerge transformed. His late work stands as a testament to the resilience of the human spirit, and to music’s enduring power to heal and to express what words cannot.

Art Pepper’s post San Quentin recordings are among the most powerful statements in modern jazz. They build on the lyricism of his early West Coast style while adding a raw, hard-won authenticity born of survival. Prison, and later Synanon, forged a deeper honesty a deeper truth tp his music. These albums aren’t just comeback stories; they are living testaments to a man who refused to be defined by addiction and prison, and who found both redemption and transcendence through the language of jazz.